What Were Dinosaur Claws Used For? Functions Beyond Fighting

Date:2025/12/20 Visits:738

When people imagine dinosaur claws, the image is often dramatic: sharp talons slashing through the air in a life-or-death battle. While some dinosaurs certainly used their claws for combat, fighting was only one chapter in a much larger story. Fossil evidence shows that dinosaur claws served many practical purposes, from feeding and climbing to nesting and environmental interaction.

When people imagine dinosaur claws, the image is often dramatic: sharp talons slashing through the air in a life-or-death battle. While some dinosaurs certainly used their claws for combat, fighting was only one chapter in a much larger story. Fossil evidence shows that dinosaur claws served many practical purposes, from feeding and climbing to nesting and environmental interaction.

Understanding how dinosaurs used their claws helps paleontologists reconstruct how these ancient animals lived, moved, and survived. Far from being simple weapons, dinosaur claws were versatile tools shaped by evolution to meet a wide range of daily needs.

What Were Dinosaur Claws Made of

Dinosaur claws were not just bare bone. Like modern reptiles and birds, most dinosaurs had claws composed of a bony core covered by a keratin sheath. Keratin, the same material found in human fingernails, allowed claws to grow longer, sharper, and more durable than bone alone.

Dinosaur claws were not just bare bone. Like modern reptiles and birds, most dinosaurs had claws composed of a bony core covered by a keratin sheath. Keratin, the same material found in human fingernails, allowed claws to grow longer, sharper, and more durable than bone alone.

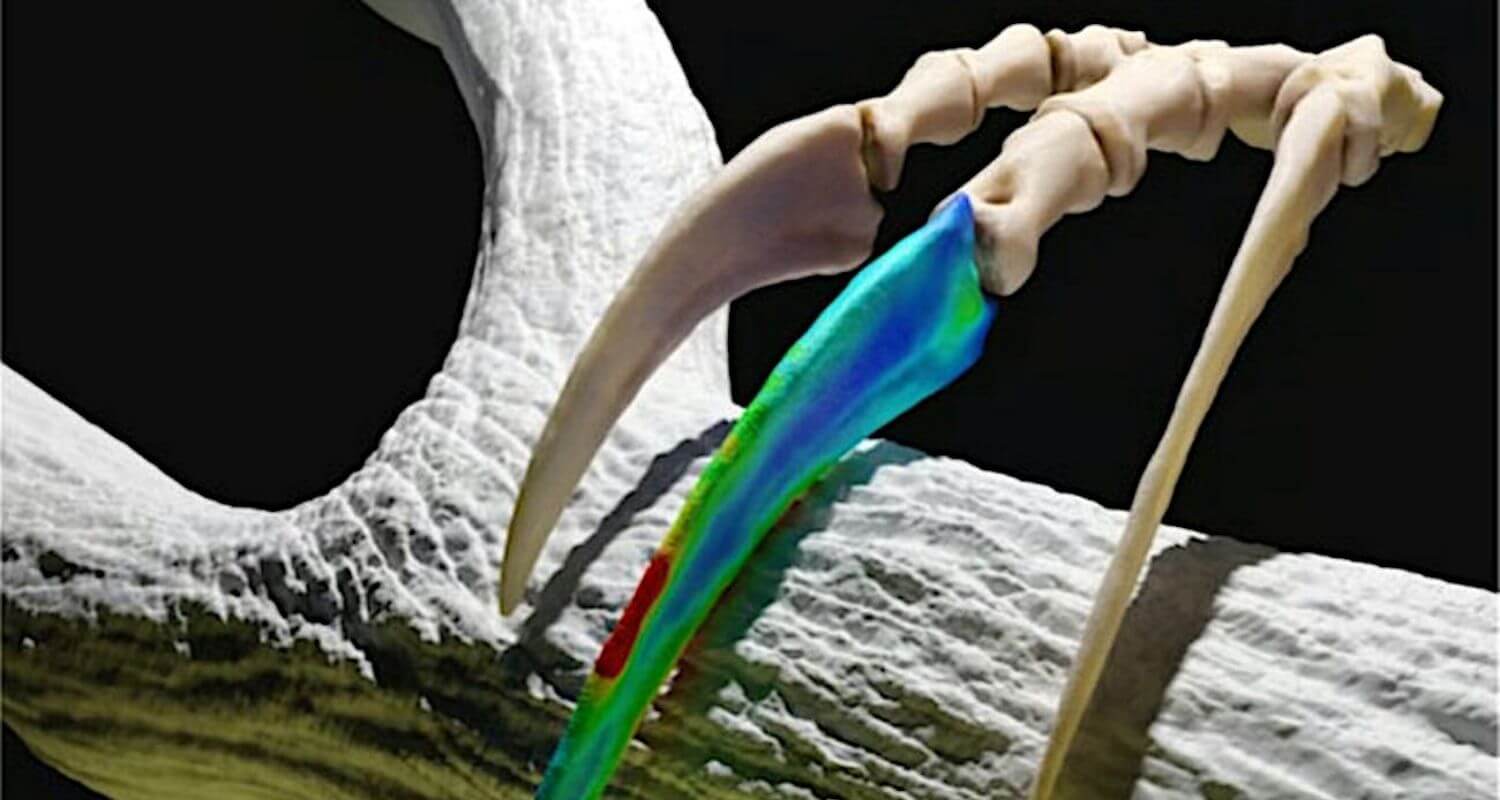

The shape and curvature of claws varied significantly among species. Some were short and blunt, while others were long and strongly curved. These differences are important clues. A sharply curved claw often suggests grasping or climbing behavior, while flatter, broader claws are more suited for digging or interacting with the ground.

Although keratin rarely fossilizes, scientists can estimate claw size and shape by studying the preserved bone underneath. This method has revealed that many dinosaur claws were not optimized for fighting at all.

Claws as Tools for Feeding

Grasping and Holding Prey

Grasping and Holding Prey

For carnivorous dinosaurs, claws played a key role in feeding. Instead of simply slashing, many theropods used their claws to grip and restrain prey. Species like Velociraptor likely relied on their enlarged toe claws to pin prey in place while delivering bites.

This gripping function reduced the need for prolonged combat. Once prey was immobilized, the dinosaur could feed more efficiently, conserving energy and reducing the risk of injury.

Digging for Food

Not all dinosaurs hunted large animals. Many omnivorous and herbivorous species used their claws to dig for food. Fossil evidence suggests some dinosaurs scratched at the ground to uncover insects, roots, or buried vegetation.

Broad, sturdy claws are especially common in species believed to have foraged frequently. These claws functioned much like the digging claws of modern anteaters or armadillos, showing that feeding strategies among dinosaurs were more diverse than often assumed.

Claws for Climbing and Movement

Some small dinosaurs, particularly feathered species, show claw shapes similar to modern climbing animals. Strong curvature and sharp tips suggest these dinosaurs may have climbed trees or clung to rough surfaces.

Some small dinosaurs, particularly feathered species, show claw shapes similar to modern climbing animals. Strong curvature and sharp tips suggest these dinosaurs may have climbed trees or clung to rough surfaces.

Claws also contributed to balance and stability. When moving across uneven terrain, claws helped dinosaurs maintain traction. This was especially important for lightweight species and young dinosaurs navigating forests or rocky environments.

Modern birds provide useful comparisons. Many birds use claws not only for perching but also for landing, climbing, and manipulating objects. These behaviors likely have deep evolutionary roots in dinosaur ancestors.

Defense Without Direct Combat

Claws were not always used to attack. In many cases, they functioned as deterrents. Large, visible claws could make a dinosaur appear more threatening, discouraging predators or rivals without physical confrontation.

Claws were not always used to attack. In many cases, they functioned as deterrents. Large, visible claws could make a dinosaur appear more threatening, discouraging predators or rivals without physical confrontation.

Raising the forelimbs, spreading the claws, or making sudden movements may have been enough to avoid a fight altogether. From an evolutionary perspective, avoiding injury was often more beneficial than winning a battle.

This idea helps explain why some dinosaurs evolved impressive claws that seem impractical for sustained fighting but highly effective for intimidation.

Nesting, Digging, and Environmental Interaction

Claws played an important role in shaping the dinosaur environment. Fossilized nesting sites suggest that some dinosaurs used their claws to dig shallow pits for eggs or clear debris from nesting areas.

Claws played an important role in shaping the dinosaur environment. Fossilized nesting sites suggest that some dinosaurs used their claws to dig shallow pits for eggs or clear debris from nesting areas.

Digging behavior also helped dinosaurs regulate temperature, access shelter, or create resting spaces. These interactions show that claws were essential for survival beyond hunting and defense.

Such behaviors are still observed in modern animals, reinforcing the idea that dinosaurs were active, adaptable creatures rather than purely aggressive predators.

Specialized Claws and Evolutionary Adaptations

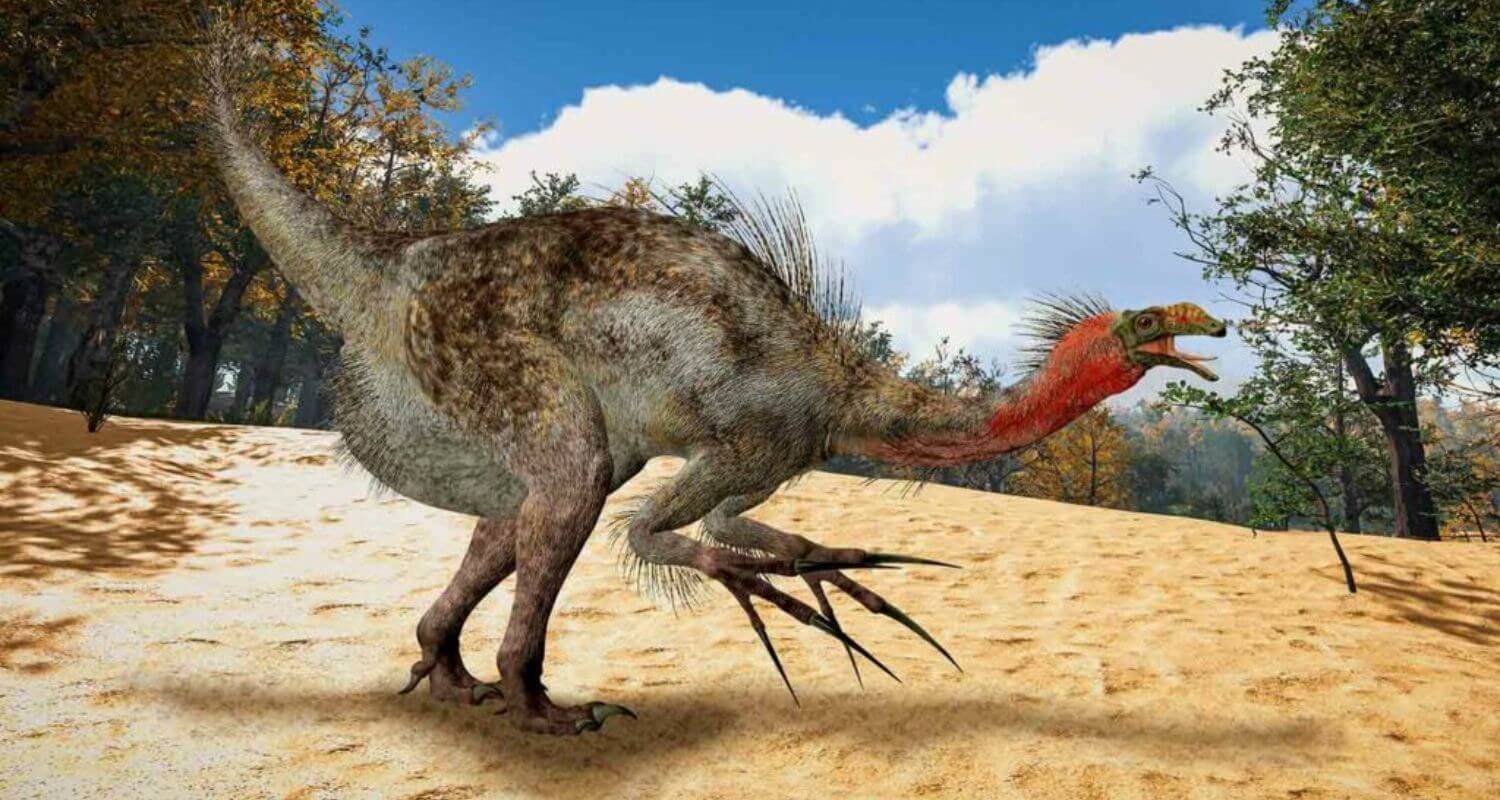

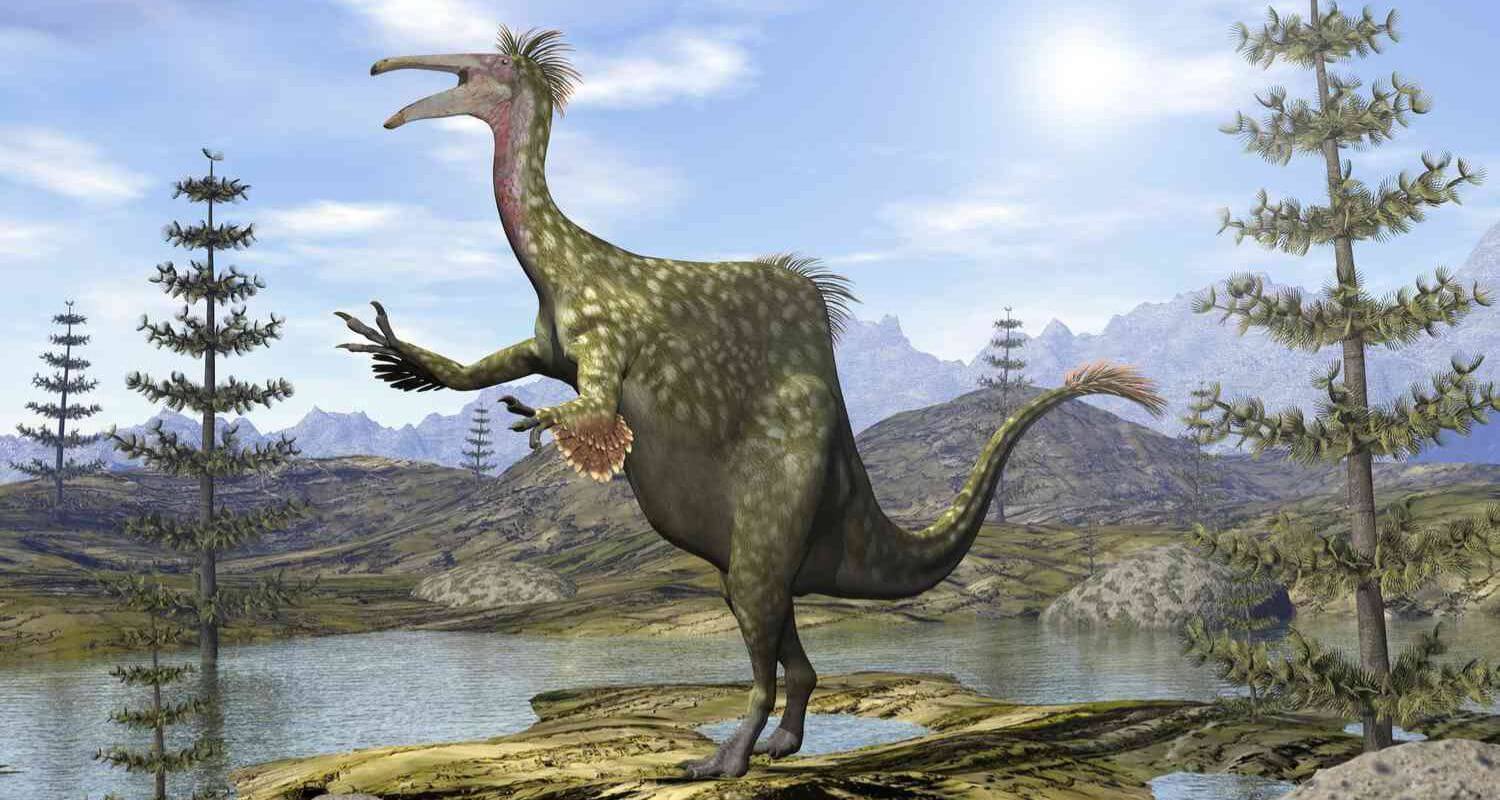

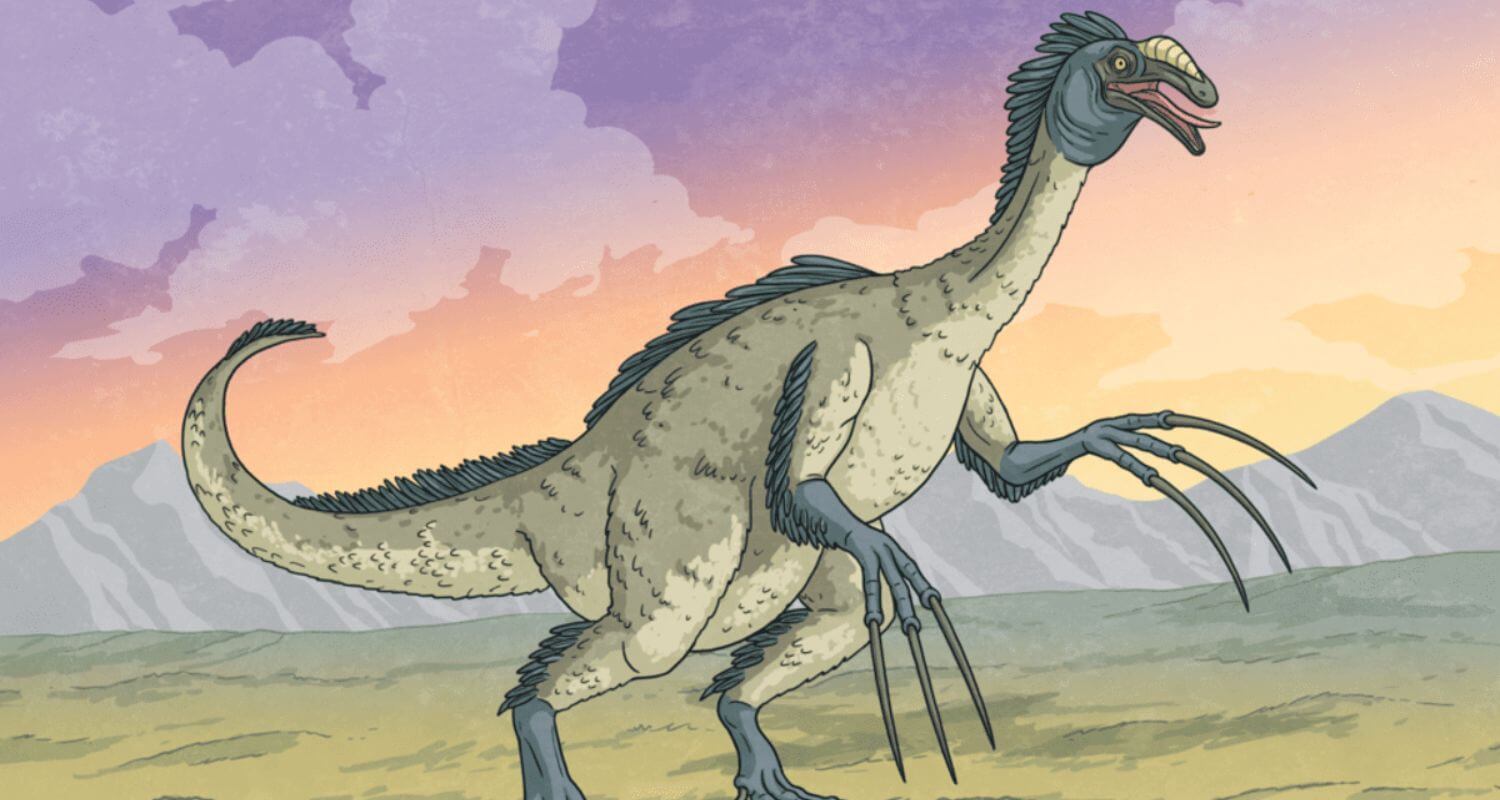

Some dinosaurs developed extremely specialized claws. Therizinosaurus is a famous example, with forelimb claws reaching over one meter in length. These claws were too long and fragile for effective combat, leading scientists to believe they were used for feeding, such as pulling vegetation closer or stripping leaves from branches.

Some dinosaurs developed extremely specialized claws. Therizinosaurus is a famous example, with forelimb claws reaching over one meter in length. These claws were too long and fragile for effective combat, leading scientists to believe they were used for feeding, such as pulling vegetation closer or stripping leaves from branches.

These unusual designs highlight how evolution favors function over appearance. Even the most dramatic claws likely evolved to solve specific environmental challenges rather than to dominate in fights.

What Dinosaur Claws Reveal About Behavior

By studying dinosaur claws, scientists gain valuable insights into diet, habitat, and daily behavior. Claw shape, size, and wear patterns help reconstruct how dinosaurs moved through their environment and interacted with other species.

By studying dinosaur claws, scientists gain valuable insights into diet, habitat, and daily behavior. Claw shape, size, and wear patterns help reconstruct how dinosaurs moved through their environment and interacted with other species.

Claws also play a key role in understanding dinosaur ecosystems. They reveal predator-prey relationships, feeding strategies, and even social behaviors, offering a more complete picture of prehistoric life.

FAQs

Were dinosaur claws sharper than modern animal claws?

Were dinosaur claws sharper than modern animal claws?

Some dinosaur claws were extremely sharp, but many were comparable to those of modern birds and reptiles, especially when covered by keratin.

Did herbivorous dinosaurs have claws?

Yes. Many herbivorous dinosaurs had claws used for digging, feeding, and environmental interaction rather than combat.

Which dinosaur had the most unusual claws?

Therizinosaurus is often considered the most unusual due to its massive, elongated claws, which were likely used for feeding rather than fighting.

Conclusion

Dinosaur claws were far more than weapons. They were multipurpose tools used for feeding, digging, climbing, nesting, movement, and display. Fighting was only one possible function among many.

Dinosaur claws were far more than weapons. They were multipurpose tools used for feeding, digging, climbing, nesting, movement, and display. Fighting was only one possible function among many.

By looking beyond combat, we gain a richer and more accurate understanding of dinosaurs as complex, adaptable animals. Their claws tell a story of survival, innovation, and interaction with the world around them, a story written in bone, keratin, and deep time.